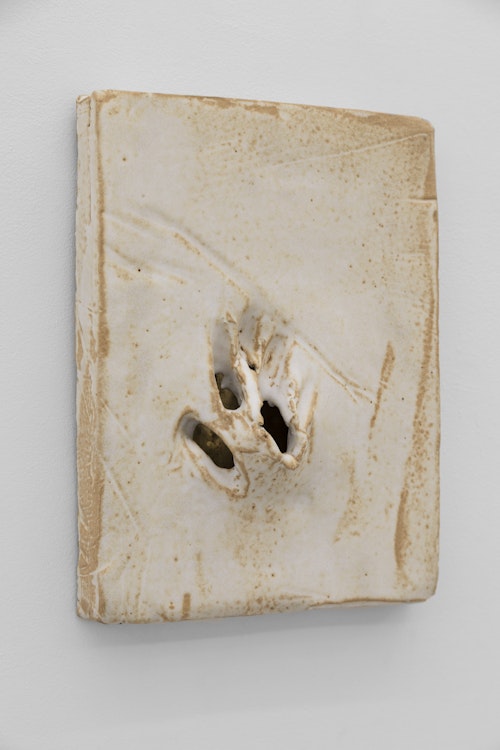

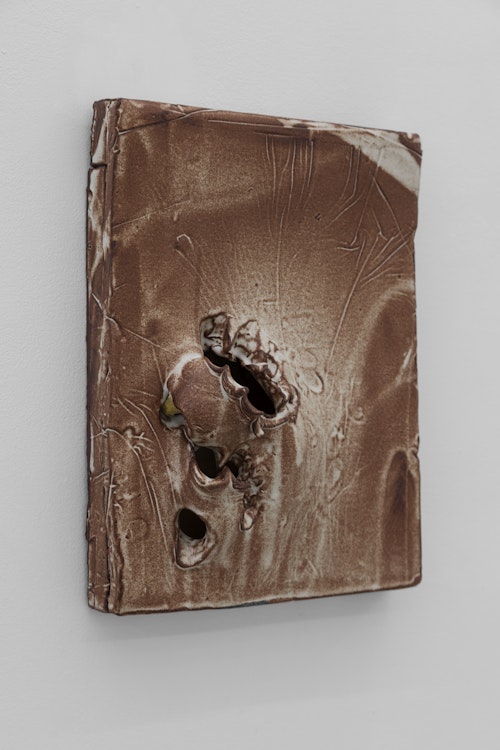

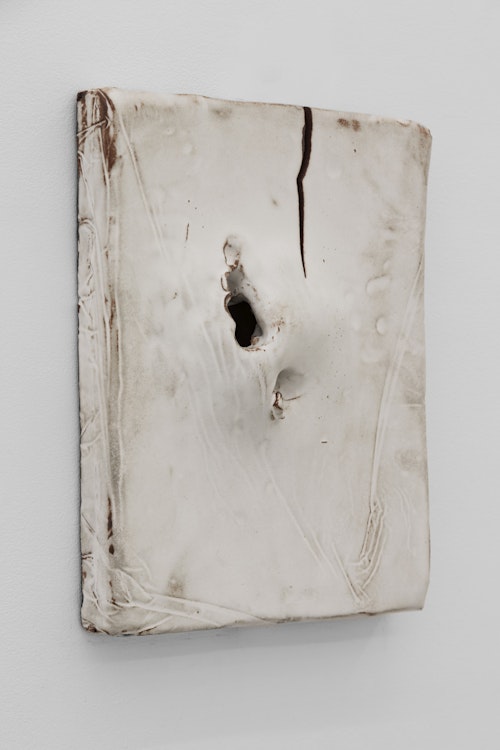

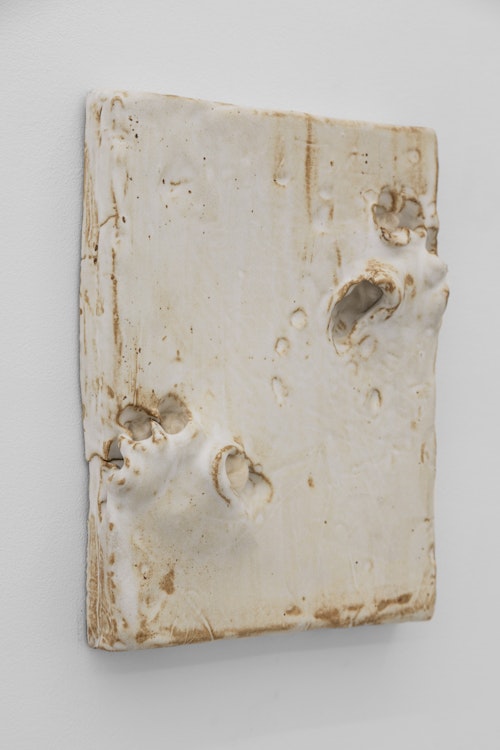

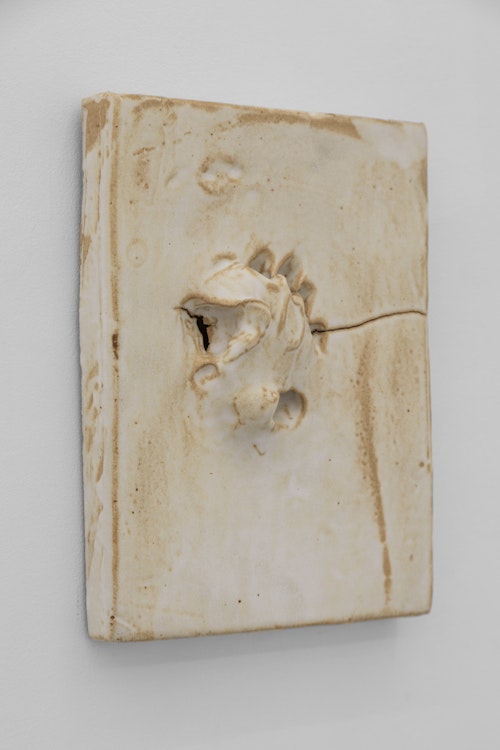

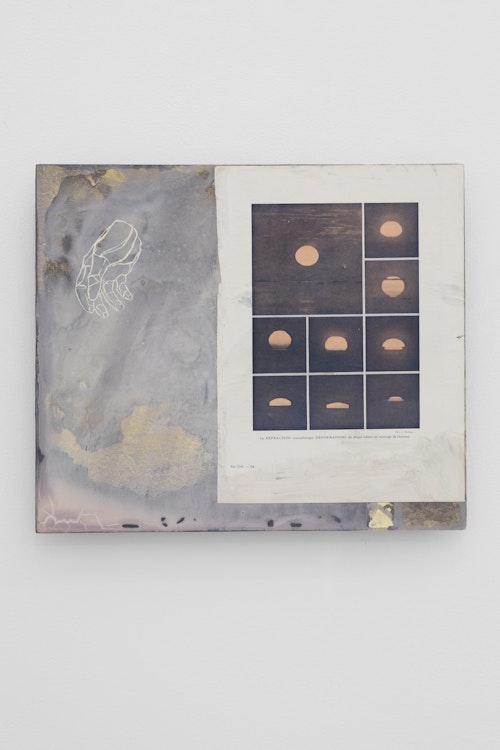

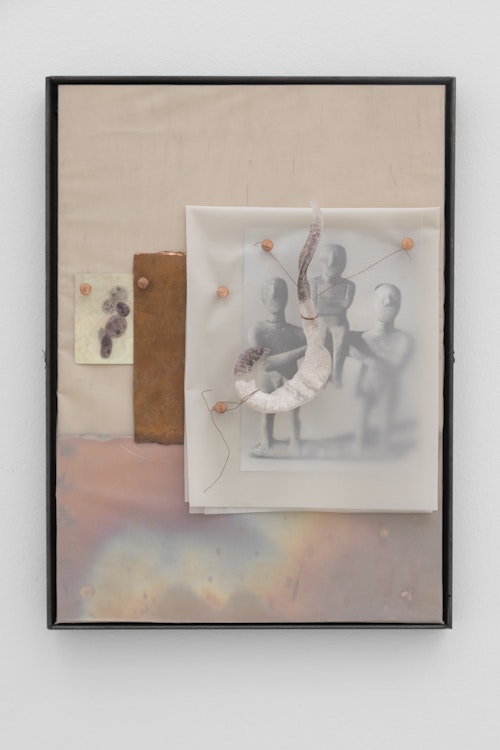

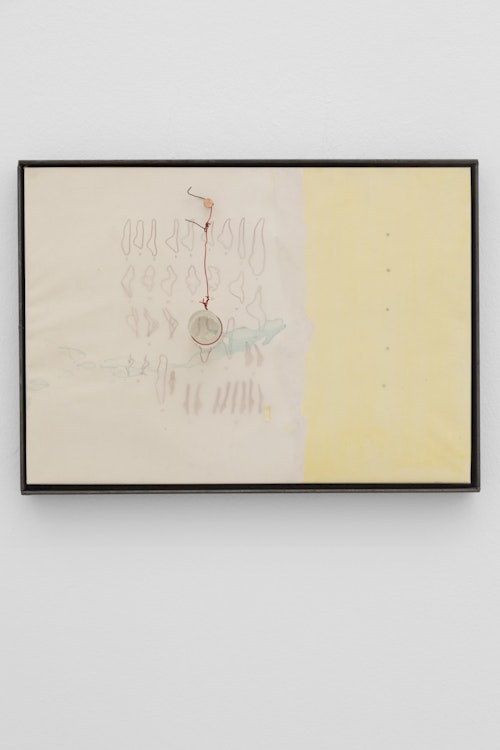

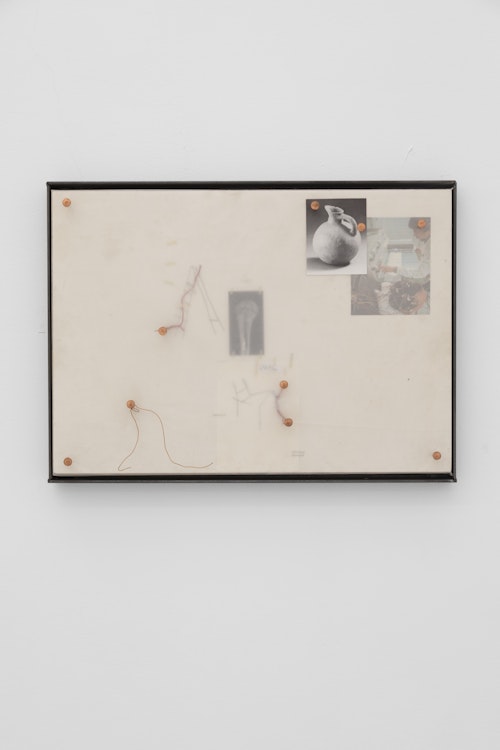

Whether it’s a memory of human activities (art, industry) or a memory of gestures, there’s a desire to veil and reveal what makes sense in order to understand - or at least to question - our origins and the challenges we face. If we look closely, we see hollows, open hands, sketched lines, happy accidents that confront us with the idea of incompleteness. Faced with the work of mountaincutters, we come to ask ourselves “what is a finished thing?”. In our capitalist societies, we talk about “finished” products. The artists focus more on the process than the result, showing us that vagueness, vulnerability, chance and doubt are the very essence of life. So it’s hardly surprising that a series of their works is entitled Objets incomplets. This underlines the impermanence of all things and the continuous evolution of the living and the non-living.

Living things (and the environment) are inevitably called upon to transform and decline before finding a new form. There is a certain analogy between the practice of mountaincutters and the studies of the anthropologist Philippe Descola, who dismantles the anthropocentric view of an “environment that societies must shape in order to acquire an identity and a historical destiny”. The idea is rather to conceive of the interdependence of humans with the environment and in a broader sense of the living with the non-living. For instance, to conceptually integrate a mountain as a member of a collective, to understand that everything is a question of balance, of shared energy and that there are roots common to a group of humans and non-humans.

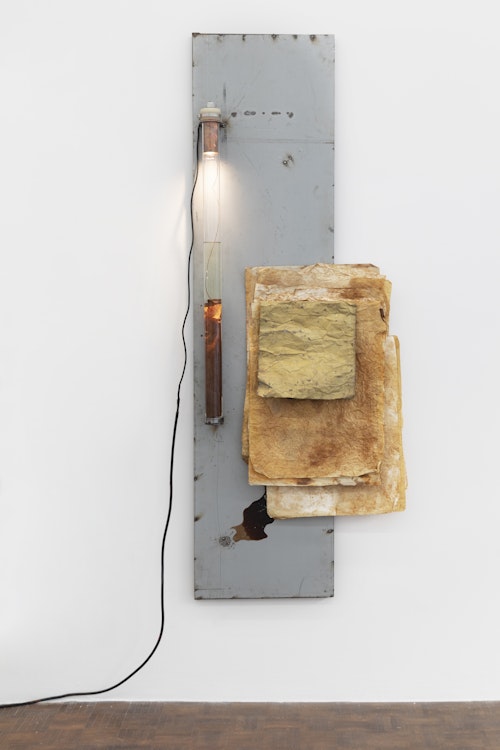

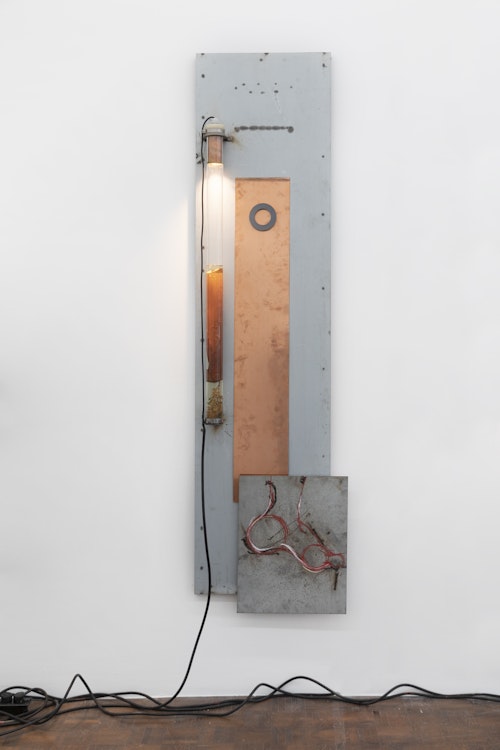

This anthropological aspect of the work seems just as relevant as certain artistic references (Arte Povera, Joseph Beuys, Ana Mendieta) that emerge through the use of physical forces or properties (magnetism, conduction), of industrial or natural elements with specific properties (copper, steel, brass, but also kapok - known as plant wool - kakishibu, etc.), the relationship between craft and industry, or references to the genius of living organisms (bees, pollen, algae, fruit), etc.

Beyond the formal issues, a strong literary and poetic component runs through the entire work. Admittedly, its presence is more subtle, but it is nonetheless pervasive. Some of the works also generate a possible political reading, such as Objet de lutte et de travail (Object of struggle and work). This vertical sculpture, which counterbalances the recurring horizontality of other groups of works, questions the nature of the hand gesture: is it harvesting, offering or intertwining wrists? Through this powerful work, visitors will be able to ponder the poetics of resistance that underlie the entire body of work. By constantly searching for points of tension, fusion and pressure in the materials, mountaincutters bring us to the threshold of a place that seems in constant equilibrium.