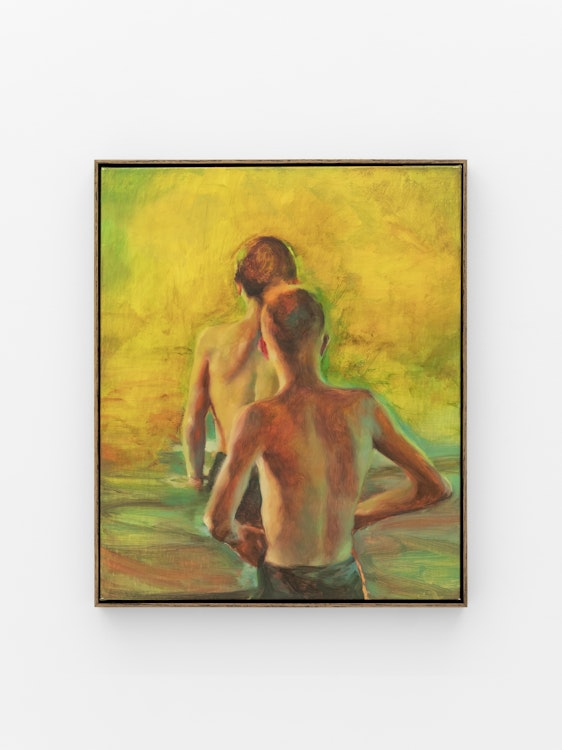

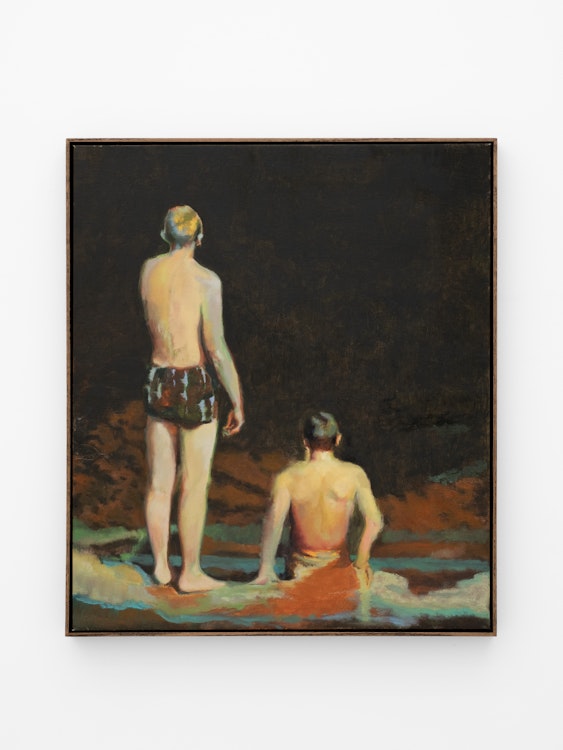

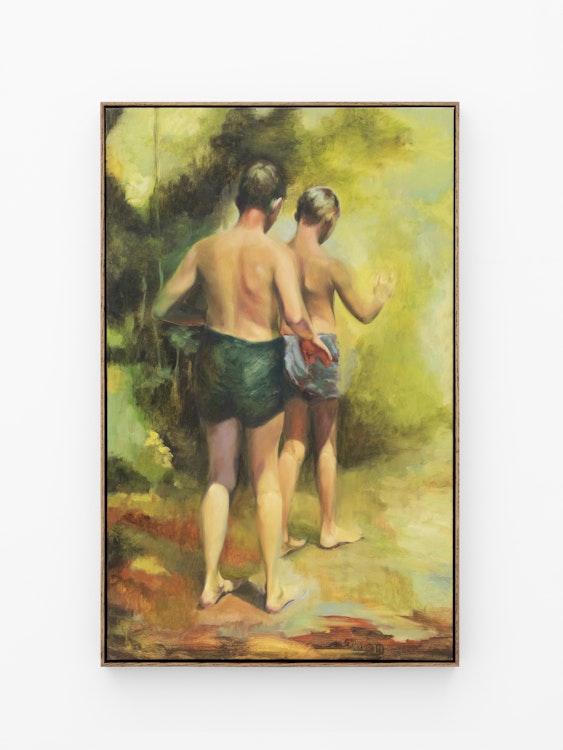

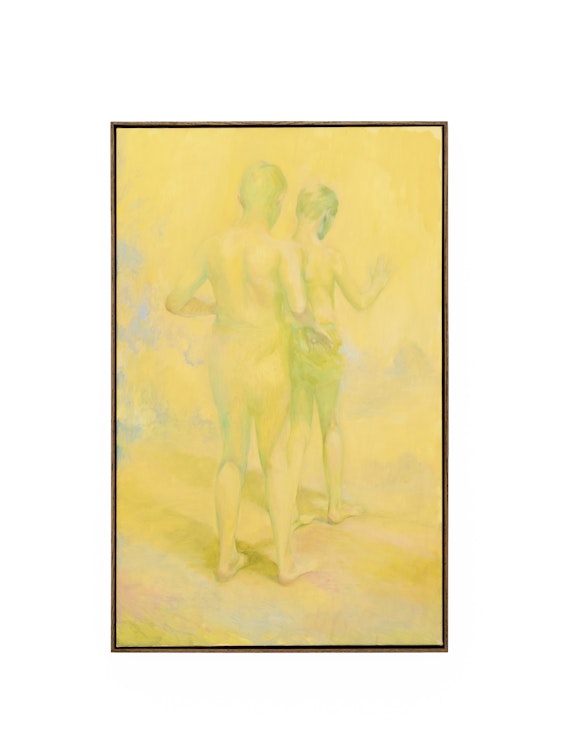

What do we see? Men and women, fairly young, partly naked, painted from behind or in profile, against a backdrop of nature that is ever present, but almost invariably abstract, undefined, impenetrable. It is Elsewhere. A place of exile? Somewhere mysterious in any case, a realm more organic than mineral, where the usual points of reference have been erased. A space we cannot locate, but full of potential fictions: what happened; what is about to happen?

The range of colours is dramatic with accentuated hues: yellows, blues, reds and greens are stretched to their garish limits. Paradoxically, the paintings’ silence, their whispers and tacit understanding, are confronted with a forceful affirmation, almost a scream, portrayed in the colours’ intensity. The density of colour reinforces the idea of an impossible world, a world of dreams, potentially hostile, into which the painter enters cautiously, without bearings, feeling the way with his fingertips.

The human figures painted by Christopher Orr seem to be hovering on the edge of a vast and unknown, yet attractive world. Orr invites us to go beyond appearances, to question the diurnal. As we look at these paintings, we have an ever-increasing sense that the characters can see things we cannot. The painter as a clairvoyant? A very nineteenth century concept that could be reinterpreted in the light of the world that lies ahead, of an uncertain future.

The characters are subjected to the implacable grandeur of nature, they seem to be witnessing a natural disaster or bracing for an exceptional event (a wave, a gesture, an action…), and this suspension of time brings a powerful tension to the composition. There is an interesting movement between the appearance of something, almost an epiphany, and the saturation of the horizon, the saturation of the colours, the positioning of the characters, which prevent us from having the slightest inkling of what is happening. Waiting without hope.

Ultimately, these works possibly question the art of painting itself: painting as matter and painting as action. Orr shows us characters who look at the painting – literally. We see them from behind, staring at the painted landscape, facing a great expanse; this area of paint where nothing is yet defined. Technically, the effects of blurring, of diffusion – of contamination almost – contribute to the strangeness of the scene. The undefined is a rich vein on which to draw. Is this an indirect allusion to the distortions of memory, the blur of recollection?

Beyond this interpretation, how can we not also see a metaphor for our very existence? The horizon, forever coming together and falling apart, is metaphysical in nature. Humankind is faced with destiny, which it does not understand but will discover. We seem to be entering the dark strata of consciousness, which gives these works a Shakespearean feel. As for the display, it underlines the repetitions; some images recur from one room to another in an obvious variation. As if we were witnessing a stuttering reality, the birth of something. In spite of repetition, things are always different.

Confronted with these works, viewers are tempted to imagine a silent dialogue that the painter is insidiously engaged in: a “dialogue of the I and the great terrestrial Other” as Yves Bonnefoy says of Edward Hopper. It is a painting of paradoxes: a painting that shows our inability to speak to one another, while provoking commentary and interpretation. Orr paints a space that speaks of absence but reveals what is human. His work is flooded with light, yet so luminous that the characters and gestures fade into the void.