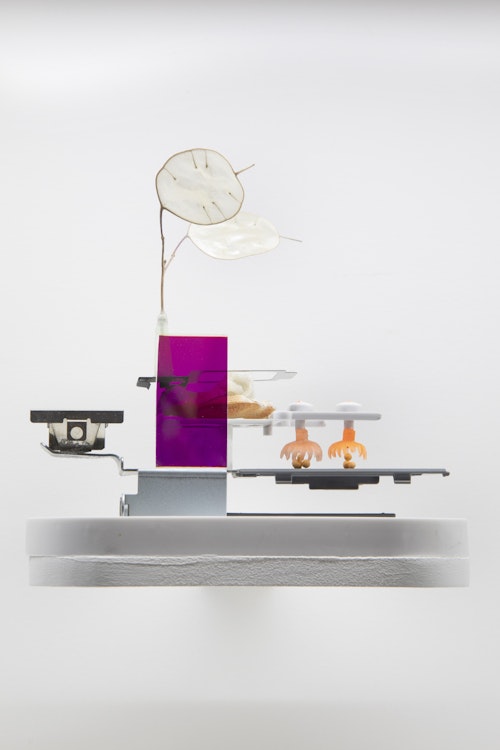

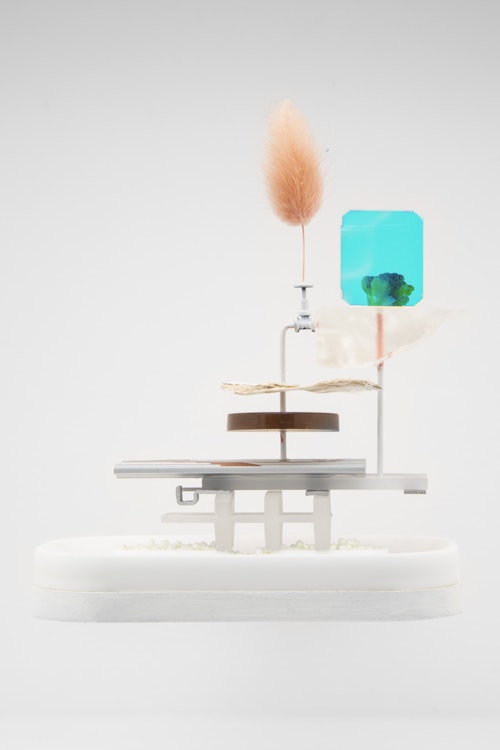

Meticulous in the extreme, Massoulier assembles a wide range of disparate elements to create organised entities that throw open a host of different questions. Whether through miniaturised constructions or more imposing installations, he questions the passage from the inert to the living (from amino acids to organised cells), the place of humankind from a macrocosmic point of view, but also the incessant technological drive (hence the title of the 5G and CriSpr series), by using scientific methods: he tests, observes, analyses, deconstructs, reconstructs, tries again, learns from errors and anomalies to finally reach a form of order within disorder.

Massoulier has created solid, referenced works that build on current environmental issues and develop narratives – whether utopian or dystopian – questioning the times to come. He shows that science fiction is not a niche sub-genre restricted to a handful of fans of apocalyptic cyberpunk or biotechnology. He shows that tomorrow’s world will be even more submerged in tools and crutches than today’s, with artificial intelligence, nanotechnology, intelligent prostheses and robots shaping our environment. He shows the multiple paradoxes of a society that promotes the object and the overpowering artefact (just one example: the complexity of mobile phones) in the face of ever-greater dematerialisation (the flow of money, the exchange of information, archiving, etc.).

This material-immaterial relationship is present in many of his works. The emergence of matter can be seen in two large basins presented in the left and right rooms, a kind of aquarium where we imagine microscopic life proliferating on the remains of obsolete machines. We think of the vital notions of the Anthropocene, of entropy, genetic manipulation, continual disintegration (debris, humus, sand, dust – ruin), pollution and artifice.

This work deals as much with camouflage as with greed, protection as aggression, beauty as monstrosity. Faced with these works, it is easy to come to the conclusion that nature is in constant evolution and metamorphosis, that humankind is but one of the participants in the saga of life.

In fact, looking at the three Crispr in the rear room – these hybrid, organic, zoomorphic forms including carapace, mandibles, stings, monstrous appendages – one can reflect on the timeline of life and our position on it. What is the human species, compared to bacteria, trilobites, or even certain modern reptiles?

Massoulier’s installations reveal many references to animals, but also to plants and minerals, whether mutated or contaminated. They contain a stratification of information. Volcanic rocks from Santorini, for example, rub shoulders with fossilised wood, evoking the slow but inexorable movement of the earth’s crust and its depths. Nature here is both subject and material, it integrates or absorbs human inventions – dichroic glass, plastic, electronic waste, etc.

His work is the fruit of an inspired search, tending towards an exploration of origins and finality. While always including a pinch of humour in his work, as well as a meticulous aesthetic reminiscent of the Japanese floral art of Ikebana, Massoulier invites us to think and take position on questions of ethics (how far can we go in the manipulation of life?), politics (the role of capitalism in the destruction of the earth system), mythology (original myths, the Golem, the minotaur, the apocalypse), and teleology (what will be the outcome of the human species?).

Images by Alice Pallot