Time is patient. It erodes. It wears down memory in a slow and implacable advance. You could say that such an erosion process is essential to the mind; that memory continuously sheds fragments of life, allowing the brain to be stimulated on other planes and to make new connections. To open this exhibition, we have chosen to display a sculpture by Goshka Macuga above the rest. It is a vase-portrait of Sigmund Freud, who thus becomes a guiding figure for visitors. The sedimentation of the mind – it is a concept that would have resonated with Freud.

The room on the left displays another work by Goshka Macuga, the International Institute of Intellectual Co-operation, a large-scale installation in the form of a molecular structure. A vast arrangement of bronze heads of famous figures is interconnected by copper rods; an intellectual cooperation suggesting a hypothetical exchange of ideas between illustrious figures: Madame Blavatsky (an esoteric spiritualist and founder of the Theosophical Society) is on the ceiling, conversing with Charles Darwin, placed centrally, like an energy conductor, in connection with Frankenstein, who himself establishes a horizontal relationship with the Indian poet Rabindranath Tagore. Pico della Mirandola, Italian Renaissance philosopher and theologian, remains isolated, cut off but not beyond reach. Macuga’s arrangement develops an incongruous but legible constellation of narratives.

Namsal Siedlecki works like an alchemist, attracted by popular culture, the history of art and civilisations, and by both ancestral and contemporary ways of producing images. Plunged into an electrolysis bath, replicas of a Gallic ex-voto statue from the 1st century BC are gradually stripped of their copper to become barely recognisable silhouettes. Removed from the bath, the various replicas (anodes entitled Viandante – travellers) are exposed as sacrificial relics, in the sense that they have metamorphosised – sacrificed themselves – in favour of a cathode, which receives their copper through the magic of electrolysis, and continues to grow into a shapeless form of copper nodules and blisters. These ex-votos were originally an offering to the Celtic divinity, Maponos, associated with the cult of fertility and prosperity.

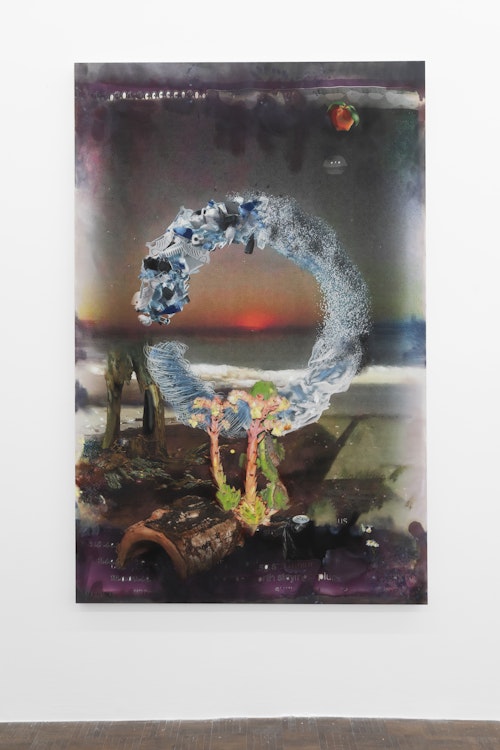

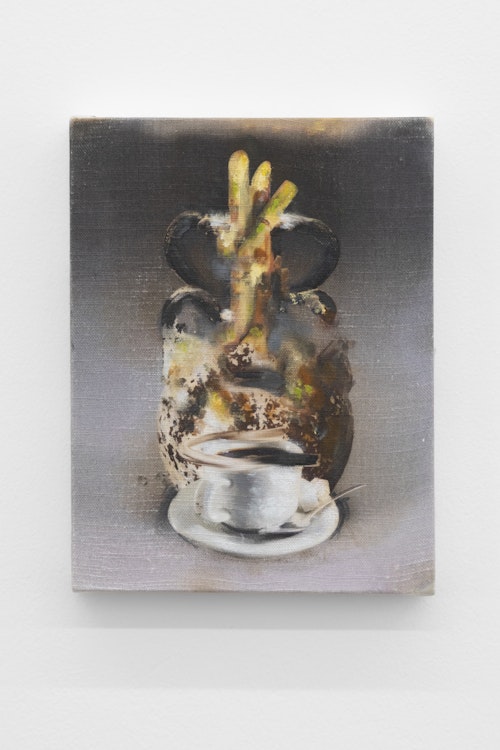

In the room to the right, a video and five paintings by artist Gaspar Willmann offer a paradoxical archaeology, combining past, present and future on the same plane, and under the generic title of JUMAP (the French acronym for Juste Une Mise Au Point (des plus belles images de ma vie) – ‘Just focusing on the most beautiful images of my life’). Starting with images found on the Internet, Willmann builds up a rich stratification of details and everyday objects, which, when articulated together, create a fragmented vision of reality. Viewers will find multiple allusions to current issues (the use of digital technology and the power of images in general, environmental issues, A.I., surveillance capitalism, etc.). Oscillating between illusion and disillusion, these works are open visions of a world in constant flux, playing on several codes and different layers of interpretation. The canvases are part printed and part painted. This combination, this incessant back and forth where the eye cannot clearly detect or define the line between printing and painting, is completely in line with the very subject of the works. The endless superimpositions, transitions and shifts in the work generate a multiplicity of possible readings. “What is thinking,” asks the philosopher Michel Serres, “if not at least carrying out these four operations: receiving, emitting, storing and processing information?” This is reflected in Willmann’s work, for example in his humorous video, Vous êtes chez vous (‘Make yourself at home’), which starts off from a message mistakenly left on his phone. Listening to this message about an intrusion into a rented apartment, Willmann tracked down the advert for the apartment on the internet, recreating a fictitious space using the elements he had collected. When reality and fiction merge to the point where you no longer know which is which...

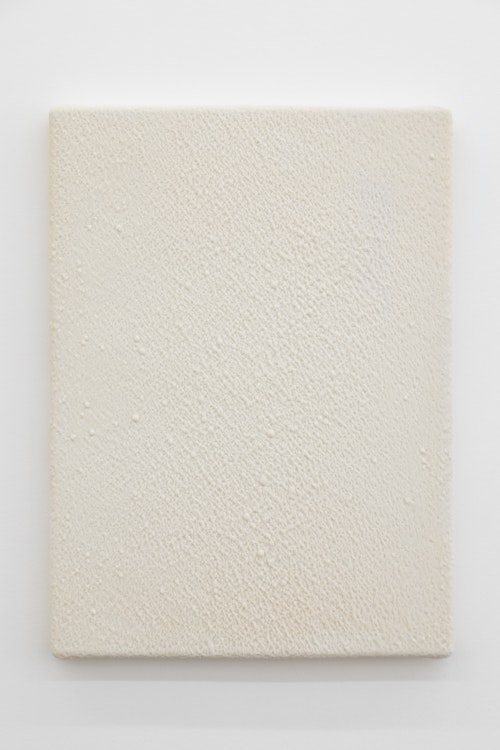

The back room displays three works by Siedlecki and a large installation by Ellen Harvey. With Gandhāra, two copper heads based on a portrait of Prince Siddhartha, Siedlecki explores the successive influences at work in all forms of artistic creation. The sculpture, which highlights a syncretic style drawing from Hellenistic, Indian and Persian cultures, has undergone successive electrolytic baths that have left visible horizontal strata. Marrying the preciousness of the metal with the harmony of the original sculpture (albeit altered), this work is a striking example of sedimentation. The intersection of cultures and civilisations is what makes the history of humanity. As for the white monochrome painting hanging nearby, Deposizione, it is made of crystals produced by a process of accelerated calcification in spring water from Saint-Nectaire in France. This water has the unusual property of petrifying any object immersed in it for several months. This textured monochrome would have taken almost 200 years to develop a similar appearance following the natural course of things. We are invited to observe a metaphorical form of time travel; to observe a work in its hypothetical future.

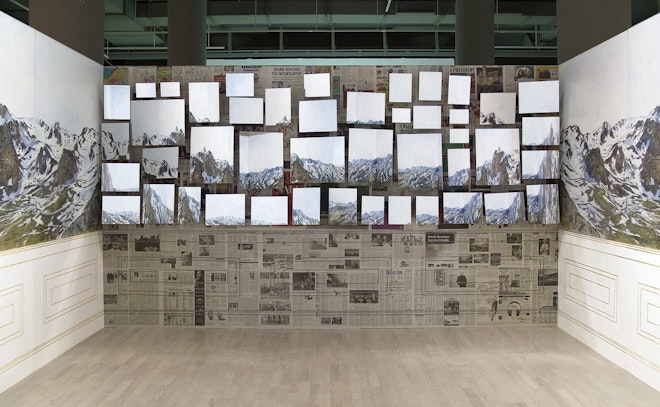

Ellen Harvey’s Room of Sublime Wallpaper is an installation that brings to life those bourgeois interiors in which the walls were plastered with genre scenes or vast landscapes. From a distance, visitors will glimpse fragments of landscape, which they gradually realise, as they get nearer, are reflections in tilted mirrors. The closer they get, the more they understand the device and the deception. What the eyes had initially understood – an ensemble of paintings set against a wall covered in newspaper – turns out to be a wall of mirrors reflecting a painting that was initially concealed. It is a kind of inverted allegory of the cave. Upon entering the small room, the panorama is revealed, and the viewer discovers the contrast between romantic grandeur and the banality of the everyday. By being in the room, the visitor’s reflection appears and destroys the idyllic representation of the mountain landscape. It is a way for Ellen Harvey to reiterate the complexity of the relationship between humans and nature; the mere presence of humans on a site can destroy the site itself. But it is also a way of demonstrating how the mind works when it sees a breath-taking site: how does it store the vision that it sees? Is it a global, panoramic view, or is it captured through fragments and details? How do we retain the beauty of a landscape? How do we reconstruct it in our minds afterwards? Which parts do we burn into our memories?

Finally, in the wunderkammer, Solène Rigou strikes a beautiful complicity between mind and body. Three works drawn in coloured pencil on wood, with names for titles, render friends’ hands in virtuoso realism. The captured moments are nonchalant or festive; shared moments of coming together. There is something of Georges Perec in this peculiar work on the flow of the ordinary. The framing cuts out the face, allowing just a partial knowledge of the subject’s identity, but we take delight in giving these hands a body, giving them a face, imagining a world beyond the frame.

Hands can also be seen more broadly as extensions of the mind. The hand, coupled with the brain, enabled humans to fashion tools allowing them to evolve from Homo faber to Homo sapiens sapiens. Standing upright encouraged the use of the upper limbs, and the evolutionary process accelerated (as the upper limbs were freed, the brain could develop, the hands could learn, etc.). Without freed upper limbs, there could be no use of tools, no development of technique. The French archeologist Leroi-Gourhan spoke of this direct relationship between the appearance of tools and the appearance of language in humans. Its development has radically changed our place and status in the global ecosystem. Let us make good use of it.

Images by Alice Pallot